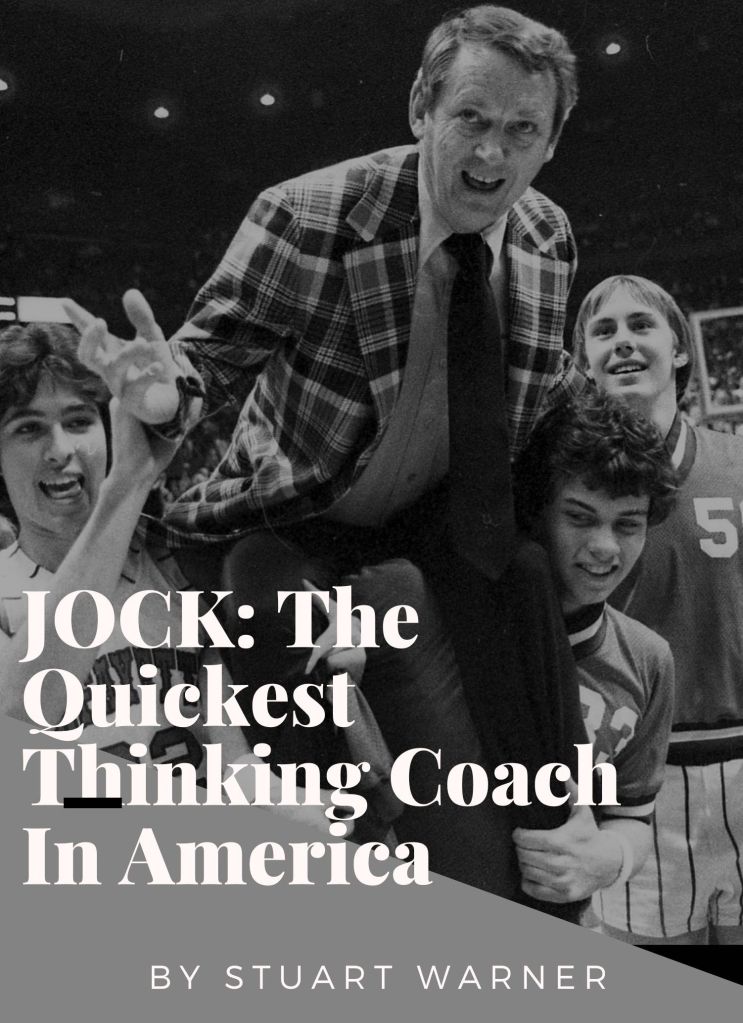

By 1967, Jock Sutherland had established himself as one of Kentucky’s most successful high school basketball coach. It was time to return to his alma mater, Lafayette High, as head coach. And he soon found two talented kids on the playground at Southland Park, Gary Waddell and Greg Austin. This is an excerpt from JOCK: the Quickest Thinking Coach in America. Available at this link.

By Stuart Warner

Fall of 1967

The Sutherlands were on the move again. In just over a year they had lived in three Kentucky cities — Cynthiana, Madisonville and now Lexington. Each time, they left behind old friends, made new ones. Neither Jock Sutherland’s wife, Snooks, nor the boys, complained. This was the life of a basketball coach’s family. They all accepted that. Charlie was 15 now, getting ready for high school. Glenn was 12, about to start the seventh grade. That summer, they moved temporarily into a house on Zandale Drive in Lexington, owned by one of Jock’s college buddies, C.M. Newton, who was away in Florida running his summer basketball camps. Newton, who had played for Adolph Rupp at Kentucky, was the head basketball coach at Transylvania University, a small private school in Lexington. One of Sutherland’s star players at Harrison County, Ronnie Whitson, had just completed an outstanding career as a four-year starter for Newton there. The two coaches had maintained a close relationship, both personally and professionally, for the past 15 years, but this was the first time they were together again in Lexington since college.

The Lexington that Jock returned to that summer of 1967 was nothing like the place he knew as a child. The combined population of the city and Fayette County had increased by more than 100,000 since 1940, now totaling almost 175,000 residents. The University of Kentucky and the tobacco and thoroughbred industries were still major employers, but IBM had brought thousands of jobs to the area, producing the latest in business technology, the Selectric type-writer. Most of that growth was south of the city limits, toward Lafayette High School. A shopping strip that stretched almost a half-mile was just a few blocks away from the Lafayette campus. And prosperous consumers discovered a new Mecca not far away — the county’s first mall, Turfland.

The baby boomers were now in their teens, forcing rapid expansion of the county’s school system. When Sutherland attended Lafayette, it was the only public white high school in the county system. The county closed its only black school, Douglass High. But Bryan Station High School on the north end of the county opened in 1958. And by 1965, Lafayette’s district was still so large that another high school, Tates Creek, was constructed in the southeastern corner of the county. Even with the split district, Lafayette was the largest school in the state, educating 2,200 students in grades 10 through 12.

These were not farm kids with chores to do. They had plenty of time for recreation.

Summer days found hundreds of them congregating at Southland Park, a 50-acre patch of land surrounded by a sea of three- and four-bedroom, all-brick homes on quarter-acre lots. The park’s new Olympic-sized pool was so crowded that you couldn’t swim. You just stood in the water and ogled all the teenage flesh splashing around you. Nobody seemed to mind.

There was a Little League baseball field at one end of the park and a full- size diamond for Pony League, American Legion and slow-pitch softball at the other. In between was a full-length, lighted basketball court where the sweat poured almost every night. Younger kids got to play early in the evening, but only the area’s best white high school and college players got into the game after the sun went down.

It didn’t take Sutherland long to find Southland Park. And two kids he found there stood out — for much different reasons; two kids who craved someone like Sutherland in their lives — for much different reasons.

The first time Jock saw Greg Austin, the young athlete was bare-chested, wearing a German helmet and running away from several animated girls at Southland. Austin seemed to embrace the free spirit style of the era. We all thought he was the coolest guy in the world. Austin was 6-foot-3, 180 pounds and probably the best all-around athlete in Kentucky. He was the state cham- pion in the triple jump as a junior, an all-state quarterback in football and had been the team’s leading scorer in basketball as a junior. He dated the school’s head cheerleader and played a mean guitar as well. How much more perfect could life be for a teenager in 1967? But not everything was as it appeared.

Sports was Austin’s refuge from a strained relationship with his father, who often disappeared for a year or more. Just as Sutherland was a gym rat crawling around Adolph Rupp’s early practices, Austin frequently sneaked into Ralph Carlisle’s workouts when his family lived only a long jump shot away from Lafayette High School. Like so many Kentucky kids, he couldn’t get enough basketball. Former UK star Pat Riley was his student teacher during his junior year and they spent a lot of time in the gym together. When he wasn’t playing at Southland Park with the whites in the summer, Austin would be at Douglass Park in downtown Lexington, testing himself against the city’s best black players, anything to stay away from home. Before his senior year, his mother and father finally divorced. He was searching for a male authority figure — like this new Lafayette coach who could still play full court, five-on-five with the best player at night at Southland.

Gary Waddell grew up — and up — only a few hundred yards away from the park. He was 6-foot-10 by the summer of 1967 as he prepared for his senior year at Lafayette. He was the tallest player ever in the county, but he never had reached his potential under Herky Rupp, the Lafayette coach Sutherland was replacing. Waddell had a stable family life — he needed direction on the basketball court.

Waddell scored only four points per game as a sophomore and barely averaged 10 points his junior season. He didn’t even make the All-City team. Despite his size, no one considered him a major college basketball prospect.

Until, like Austin, he met Jock Sutherland.

The three were thrilled to find each other.

In Austin, Sutherland saw the best athlete he’d coached since Keller Works at Harrison County. Austin saw a man who cared about him as a person, not just an athlete.

In Waddell, Jock saw a player who was not only taller than anyone he had coached but who had some athletic skills, a soft touch around the basket and an enthusiasm for the game. He also saw a player who was timid and needed work on the fundamentals of playing with his back to the basket.

Waddell saw a coach who immediately believed in him and instilled confidence in him. He was an avid sports page reader. He knew about Sutherland’s success at Harrison County. It meant a lot that a coach with that reputation was interested in him. He was willing to do whatever the coach asked.

Which was a lot.

Jock brought Waddell to the Lafayette gym two or three nights a week that summer. Austin usually went with them.

He didn’t need the work on his game as much as he needed the bonding.

They drilled for a couple of hours each night, without air conditioning, just the three of them, and sometimes a manager. Austin lobbed pass after pass to Waddell. The coach used a football blocking dummy to pound on the big as he turned and maneuvered toward the basket. They repeated the drill over and over. The object was to learn to move his feet without thinking, like an organ player pumping the pedals. Jock told Waddell he could stop when the drill got boring. Waddell never asked to stop. He got bruises on his upper body. The coach’s hands turned raw from holding the grips on the dummy until he got smart and bought a pair of leather gloves for protection. The coach instructed him to keep the ball high when he grabbed a rebound so that smaller players couldn’t snatch it away from him. He made Waddell run up and down the court sideways, again and again, crossing his feet back and forth to improve his agility. And he made him sweat and sweat and sweat.

By the end of the summer, Waddell looked like a different player. He and some other local players were asked to scrimmage with a Kentucky all-star team, matched against 7-foot high school All-American Jim McDaniels, who was headed for Western Kentucky University. Waddell played so well that Eastern Kentucky University coach Guy Strong, who had signed Sutherland’s star Toke Coleman a year earlier, offered the Lafayette center a full scholarship.

Waddell was flattered. It was the first time a college coach had shown interest in him. It wouldn’t be the last.

xxxxxxxxxxx

Jock wanted to buy a house on a corner lot across the street from Southland Park but decided he couldn’t afford the $25,000 asking price. He settled for a $16,000 Tudor just three doors down from the Lafayette campus, which also was expanding. The 1,000-seat gymnasium where Sutherland and his teammates dominated opponents during his senior season had been converted into a library. A new wing, the Harry L. Davis Center, had been added to the complex, housing a 2,800-seat gymnasium, the cafeteria and health and science classes. Sutherland built an office in the equipment cages off the locker room, painting it all red, white and blue, the school’s colors.

A few faculty members remembered him well. Some too well. Thelma Beeler, the drama teacher who had developed such young thespians as Sutherland’s closest friend in high school, Harry Dean Stanton, and Jim “Ernest” Varney, still wouldn’t speak to the coach she knew as Charlie. During his senior year, Sutherland’s girlfriend had a kissing scene in the senior play with the leading man. After basketball practice, Charlie found the two of them doing some extra rehearsing behind the stage curtains. A fight ensued. The leading man performed on opening night with a black eye.

The basketball team had changed, too.

The program may have lost the respect that it once had, but Sutherland wasn’t disappointed with the talent.

Besides Waddell and Austin, the Southland Park regulars included Rick Derrickson, a 6-foot-1 junior guard, who was one of Kentucky’s top baseball pitchers and was already attracting attention of the pro scouts.

Black players brought a dimension to the team that missing when Sutherland played at the school. The first stage of integration went relatively smoothly at the school after Douglass High School was closed in 1963. Lafayette had fewer than 50 black students in 1967, most of them from the rural communities in the county like Fort Springs, Jonesboro, Maddoxtown and Little Georgetown, which were all settled in the 1800s by emancipated slaves. The black players from these unincorporated areas were more like the farm kids Sutherland was used to coaching. They were used to hard work and rarely complained. Several of them played significant roles on the varsity. Senior point guard Mike Livisay, quick and smart, was the son of legendary Douglass High coach and principal Charles Livisay. Juniors Aaron Beatty and Darryl Washington were both also sprinters on the track team. Senior reserve Snake Berry, a 6-foot-2 leaper, could dunk with both hands from a standing position. He was a fearsome shot blocker.

The team lacked only one thing, Sutherland thought.

“These boys don’t have much discipline,” he told the Lexington Herald before practice began in the fall of 1967.

He got a call from Adolph Rupp Sr. the following day.

“Jack, what do you mean your players don’t have much discipline?” Rupp growled. “They played for my son. Of course they have discipline.”

Jock had been scouting opponents for Kentucky for the past couple of seasons — and Rupp always called him “Jack.” Sutherland didn’t want to alienate the Baron. He needed the extra cash. So The Quickest Thinking Coach in America had an answer that kept his part-time scouting job:

“I was misquoted, Coach Rupp. You know those newspaper guys never get anything right. Of course these boys are disciplined.”

They weren’t, though. And he set about changing that right away.

He painted a semicircle, 19 feet, 9 inches from the basket, at both ends of the court. Anyone who shot outside that line ran laps. Anyone who cursed ran laps. Anyone who didn’t hustle ran laps. Anyone who disobeyed a coaching directive was sent home. Anyone.

Jock installed the Mad Dog at Lafayette and continued to tinker with the defense. One day in practice, he used the junior varsity to run the opponents’ offense against his varsity starters.

One of the junior varsity guards had watched the Mad Dog for years. He knew that the defense had a slight flaw in it and if you made a pass at the precise moment, it would lead to an easy basket.

The first time the guard brought the ball up against the varsity defense he made the pass to a teammate who scored easily.

The coach wasn’t pleased.

The next time, the same thing happened.

“I understand that you know how to beat this defense,” the coach said, his voice rising. “Don’t throw that pass.”

The third time the guard initiated play against the defense, he saw his teammate open again. Instinct took over. He threw the pass. The ball hadn’t traveled three feet from his hands when another ball came sailing past his head.

“You sorry … ” Jock yelled. “Get out of my practice.”

The Jayvee guard, Charlie Sutherland Jr., left the gym and walked home. Snooks wasn’t happy. When Jock returned to the house that night, he wasn’t greeted at the door by a basketball coach’s wife.

A player’s mother was waiting for him instead.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Gary Waddell had never begun a season so confident. Sutherland made him the focal point of the offense. The perimeter players were no longer taking shots from anywhere on the court. Austin, in particular, sacrificed his scoring role to make the lob passes into Waddell, the passes he had thrown him hundreds of times that summer. On defense, Waddell’s size allowed the other four players to gamble for steals — if they missed, he was there to back them up. He was also mastering Sutherland’s tip drill. Instead of trying to grab every rebound, he would reach above his foes when an opponent missed a shot and tip the ball to the foul line, where Mike Livisay was usually waiting to start the fast break.

Lafayette won two pre-season games fairly handily and beat McCreary County by 16 points in the season opener.

Next up was Tates Creek. The school was only two years old, but the game became an instant rivalry. Some of the players had gone to junior high school together. Some families still had students in both schools because upperclassmen had been allowed to graduate where they started. To make matters worse for Lafayette, Tates Creek, the new kid on the block, had battered the Generals twice the previous season.

The H.L. Davis Center was overflowing with more than 3,000 fans that night. Lafayette led by as many as five points with just under three minutes to play but Tates Creek scored the final 10 points to defeat its rival for the third straight game.

Sutherland took his team’s collapse as an indication his players needed more conditioning. The next day, he let all of us junior varsity players go home early. After the varsity finished its regular practice, he had a treat for them — the 11-man break. It’s a continuous fast-break drill with the players rotating between offense and defense, from one end of the court to the other and back again. And again. And again. They would run it until they were perfect, not a bad pass or missed shot.

The more they ran, the more difficult it was not to make a mistake.

Sutherland missed his regular 6:30 p.m. dinner with Snooks and the boys. The players were still running at 7. At 7:30, at about quarter past eight, Sutherland ended the drill.

Dinner was cold when he got home. He wasn’t hungry anyway. Basketball had become an all-consuming job. During the season he never stopped thinking about the game. He was determined to return his alma mater to its former prominence. He wanted to take Lafayette to that state championship that had eluded him his senior season and in his four previous trips to The Sweet Sixteen at Gallatin County and Harrison County. He knew he had more talent on this team than any other he had coached.. If only he had begun working with them sooner. He had to make up for lost time.

Lafayette won its next five games before the Christmas break, then headed to the Ashland Invitational Tournament, where another outstanding field awaited. In the opener, Waddell outplayed Russell High’s 6-foot-8 All-Stater Tom Roberts. But in the semifinals, Covington Catholic’s 6-foot-9 twin towers, Randy Noll and Joe Voskuhl, were too much to overcome. That put the Generals in the consolation game against host Ashland, which also lost in the semifinals.

Jock had already developed quite a reputation among the Ashland fans. One year, he got so upset during a game that he got off the bench, stormed out a gym door that locked behind him, and had to pay his way back in. In December of 1965, his Harrison County players created a ruckus when they jumped into the school’s indoor swimming pool after routing the home team in the semifinals. So far this year, he had behaved himself. So far.

But late in the third quarter against Ashland, with Lafayette already leading by 20 points, junior Aaron Beatty got the ball on a fast break and instead of driving to the basket, he stopped well beyond that arc of 19 feet, nine inches, that Sutherland had painted on the team’s home court, and unleashed an errant jump shot.

The coach jumped out of his seat. Then he stunned Waddell, Austin and the others as he left the bench and started walking out of the gym. At least Jock had learned his lesson. Instead of heading toward the doors leading to the outside, he strutted into the lobby. A few minutes later, he returned with doughnut and coffee in hand. He then sat in the stands, watching the rest of the game from the bleachers.

The Ashland fans thought he was mocking them after Lafayette won 74- 52 to take the third-place trophy.

Jock said he was just hungry.

His team got the message. You never let up.

The Generals won their next two games by more than 30 points, then edged longtime city rival Henry Clay 70-68 in front of more than 7,000 fans at the University of Kentucky’s Memorial Coliseum.

Lafayette won three more in a row, but the winning streak almost ended there when highly-ranked Clark County High School came to Lexington on Jan. 26, 1968. For three quarters, nothing went right for the home team. Nothing. Jock started to walk out of the gym, another disappearing act. But it was really cold outside. As he returned, he saw an 11-year-old boy seated near the end of the bench, blowing a three-foot-long plastic horn. Sutherland walked up to the boy, snatched the horn away from him and started to blow. Not a note came out. He tried again. Still no sound. Disgusted, he tossed the horn down. The boy, Scott Warner, my younger brother who would play for Sutherland four years later, retrieved it before it rolled onto the court.

But the Lafayette players must have heard their coach’s clarion call anyway.

At the beginning of the fourth quarter, Clark County led by 16 points. Then the Mad Dog finally got loose. One steal, then another, then another. Momentum is such a fluid thing among 16- and 17-year-old athletes. You can have it one moment, and then it’s gone. The Lafayette gymnasium suddenly began rocking. The Clark County lead slipped to 10, 8, 6 … and finally, the game was tied at 66-66 with eight seconds to play.

Lafayette had the ball. Sutherland called time out. Guard Mike Livisay had been the hot shooter during the stirring rally. And Waddell, of course, was the team’s top scoring threat. Austin was the team’s No. 2 scorer, but he was having an off night, making only five of his first 15 attempts.

Who would get the last shot?

In the huddle, Sutherland called the play.

“Greg,” he said, “I want you to take it.”

On the in-bounds play, Austin broke from his position on the wing, ran his defender off a pick near the free-throw line, then arched the ball high from about 17 feet.

The shot clanked off the rim.

Overtime.

Sutherland wasn’t upset. “We’ll get ’em,” he said, patting Austin on the back.

With less than a minute to play in the extra period and Lafayette clinging to a 73-72 lead, Austin sank a free throw to put the home team ahead by two, then stole the in-bounds pass, setting up a final score for Lafayette’s 76-72 victory, improving its record to 16-2.

Austin failed to make that winning shot, but of all his athletic accomplishments, he still says that nothing had meant any more to him than the confidence his coach showed in him in those final moments of regulation. It was as if the father who was rarely there for him had told him, “I believe in you, son.”

xxxxxxxxxxxxx

Maybe this was the team. Maybe this was the year. The Generals had size, speed, experience and athleticism. They were thriving in Sutherland’s system. Waddell was no longer milquetoast in the middle. He was averaging more than 20 points and 10 rebounds per game. A lot more colleges were noticing. Tennessee, North Carolina, Florida, Auburn, Wake Forest, Alabama … almost every school in the south, save one, seemed intensely interested. Kentucky assistant Joe B. Hall showed up at a few Lafayette games, but Waddell knew that his hometown team wouldn’t offer him a scholarship, not after what happened to Coach Rupp’s son at Lafayette. Waddell didn’t mind. It was tough enough to play for Rupp. You didn’t want to be the player from a school he had a grudge against.

Lafayette’s winning streak reached 10 before the Generals got a rematch with Tates Creek. Different gym. Same result. Tates Creek won 82-75.

The next day, the players expected another round of running. Instead, Jock told them there would be no practice. They would just watch film of the previous night’s defeat. That would be easy, Waddell and Austin remember. On their bodies, maybe, but not on their minds. Every time the film showed any mistake, Jock whacked the side of the projector with a stick. A bad pass. Wham! Poor shot selection. Wham! Didn’t switch men on defense. Wham! Wham!

Again, they got the message.

Lafayette won its next four games to improve its record to 21-3. The Generals were again among the state’s elite teams, ranked No. 5 in the Associated Press Poll. Their next game was against the new No. 1 team, Louisville Shawnee, and its monster junior center, 7-foot Tom Payne. Anticipation for this match between perhaps the state’s two best big men had been building for a couple of weeks.

It didn’t happen.

Waddell twisted his ankle late in the game against Louisville Ahrens, the team’s final test before Shawnee.

The injury was worse than he first thought. The next day, he couldn’t put any weight on it at all. The doctor ruled him out for the final game of the regular season. With no one to neutralize Payne, Sutherland didn’t think his team had a chance. He tried a stall at the start of the game and it worked for a few minutes as Lafayette strolled to a 12-3 early lead. But the Generals also lost starting guard Rick Derrickson with an ankle injury and the lead quickly vanished. Payne didn’t need to do much on offense, scoring only eight points. He dominated the inside defensively, and his teammates took care of the rest as they sprinted to a 70-49 triumph.

A few days later, Charlie Sutherland Jr. recognized the look on his father’s face. Usually he saw it after a devastating loss, like to Bourbon County in the 10th Region tournament in 1963 or to Shelby County in The Sweet Sixteen in 1966. But this time he saw it before a game, before Lafayette played 10th-ranked Henry Clay in the opening game of the 43rd District Tournament. Just over a week ago, Sutherland thought he had the best chance he’d ever had to win the state tournament. But now, Waddell had missed almost 10 days of practice. He would play against Henry Clay, but how effective could he be. Derrickson, too, was still not a full strength. Henry Clay was now the only high school in the city of Lexington. Dunbar was closed the year before, and most of its best players had been relocated there. The first Lafayette-Henry Clay game that season was a classic, but Sutherland’s team was a full strength. But with his big center still ailing …

Waddell didn’t come out firing blanks. He sank his first three shots. He looked a little tired after that, but Lafayette still held a 46-44 lead late in the third quarter. Then Sutherland’s hopes for returning to his school to The Sweet Sixteen were gone in a flash. Henry Clay scored 14 straight points. The final score: Henry Clay 71, Lafayette 62. Jock’s first season back at his alma mater was done.

A few weeks later, after he watched Glasgow High win the 1968 state championship, Sutherland felt better about the season. Back at school, he walked out the gym’s back door, into a little alley between the basketball arena and the baseball field. There’s nothing quite like a warm spring day in Kentucky and this one seemed particularly special. He thought about what he had accomplished … a 21-5 record … not bad for a program that had been down for several years. He had transformed Waddell into a first-team All-State player who received a scholarship to play at Florida. Austin got a basketball scholarship to Auburn. Regulars Derrickson, Beatty and Washington would return the next season. Six-foot-7 junior Howard Jackson showed a lot of potential. If Jock worked with him over the summer like he had with Waddell …

Then he looked up. He remembers seeing his pal C.M. Newton, his former fraternity brother at UK, walking toward him from the street in front of the high school.

“Hey, boy, what’s up?” Jock yelled at him.

Newton walked closer.

“I’ve just been named the new head basketball coach at Alabama,” Newton said. “I want you to come with me as an assistant coach.”

A chance to coach in the Southeastern Conference against teams like Kentucky, LSU and Tennessee. Yet it meant leaving the school he’d worked a decade to get back to, abandoning his mission to win a state championship at his alma mater.

The Quickest Thinking Coach in America didn’t have an immediate reply.

“You’re throwing something at me,” Jock said. “I’m going to have to think it over.”

“Don’t take long,” Newton said. “We’ve got to start recruiting immediately. We’re already behind.”

Again, Sutherland took a family vote. And it was unanimous — take the Alabama job. But he needed to talk with one person — Guy Potts, the superintendent of the Fayette County schools. Jock walked to the Board of Education offices, which were adjacent to Lafayette High School.

“You brought me here,” he told Potts. “I’ll do whatever you recommend.”

“I think you should go,” Potts said. “This is your goal, your dream.”

He paused for a moment.

“But for some reason, I think you might be back someday,” Potts said. “And the Lafayette job will be here for you if you want it again.”

Leave a comment