Excerpted from Akron’s Daily Miracle (copyright 2020, University of Akron Press)

By Stuart Warner

Change was on the way to the Beacon Journal and Akron in 1986.

On Sunday, March 30, Executive Editor Dale Allen headed south on I-77 to the Akron-Canton Airport to meet Knight Ridder Vice President Larry Jinks.

“A dozen possibilities passed through my brain, most of them making no sense at all,” Allen wrote in his unpublished memoir about the summons from his boss. Was he being moved out of the newsroom? To another paper? Maybe they were going to fire him.

But there was one possibility he hadn’t considered: He was offered the job as editor of the paper. Corporate had been unhappy with the bickering between Editor Paul Poorman and General Manager Jim Gels and was replacing both of them. Gels was shipped to the company’s paper in Duluth, Minn., to replace publisher John McMillion. McMillion was coming to Akron as the paper’s first publisher since Ben Maidenberg retired in 1975. Poorman was offered another job at the Beacon, but decided to resign. The job was Dale’s if he wanted it. He did.

Tim Smith, who had been promoted to managing editor by Poorman, also left to teach at Kent State as Allen ascended to the top spot.

“Dale sat between Tim Smith and Paul Poorman, not fully in charge of the newsroom,” recalled John Greenman, then the Beacon’s assistant managing editor for metro news. “When Smith and Poorman left, Dale was free to reframe the newsroom to take advantage of the people he’d hired and promoted and, as importantly, to reorient (or relieve) veterans from the Kent State coverage, who’d become smug and lacked intensity.”

Dale found just the right person to bring a new intensity to the newsroom at his former paper, the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Larry Williams was a rising star in Knight Ridder. His degree was in engineering, but his passion was journalism. He joined the Inquirer in 1971, advancing to business editor, where he supervised two Pulitzer Prize-winning projects, including the coverage of the near-disaster at the Three Mile Island nuclear plant. “He turned what had been a small undistinguished business news department into one of the nation’s best,” said Gene Roberts, legendary former editor of the Inquirer. “But his influence on the paper went far beyond business news into major investigative reporting and the design and layout of the paper. His talent and drive were exceptional.”

Tim Smith had supervised only metro news and the copy desk as managing editor. “Dale … delegated vast authority” to Williams, Greenman said. “Larry would not have come to Akron without it. Indeed, he turned down the job of Sunday Business Editor of the New York Times to come to the Beacon Journal.”

I was the Beacon’s local columnist, writing Warner’s Corner, when Larry arrived. I was known mostly for wearing a hat and writing about Stowbillies, Kenmorons and empty storefronts in Akron’s downtown. Not Larry’s kind of journalism. And, oh, yes, I constantly took pokes at “Muffy” and “Buffy” and everyone else who lived in the affluent suburb of Hudson, where Larry and his family bought a rambling Colonial-style home. My Hudson humor was often not appreciated by the village’s newest resident. And more than once he killed a column with questionable taste, like the time a politician in Columbus proposed hiring prostitutes to tell people about the danger of AIDS. I innocently wondered how they would fill out an application, including the question, “Position Desired?”

I had no idea of the impact Larry’s hire would have on me and all of us at the paper and, perhaps, on the city of Akron.

Within weeks after Larry joined the paper, financier Sir James Goldsmith bought his first shares of stock in the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company. This was a man who described himself as “a bringer of change.” In Larry Williams, he met his match.

**************

On Monday afternoon, October 7, Business Editor Doug Oplinger noted a sharp rise in Goodyear’s stock. Oplinger grew up in nearby Springfield Twp., then returned to work for the Beacon Journal after graduating from Northwestern University. He started in Akron as a metro reporter, moved to the business desk when it consisted of only three people and had been promoted to business editor just a few months before Larry Williams arrived. Oplinger stayed at the paper until he retired as managing editor in 2017 after 46 years at the Beacon.

His institutional knowledge told him something was up when the stock closed at a 15-year high of almost $37 at the end of the trading day.

“In Akron, just about everybody had a relationship with a tire company,” Oplinger told Bowling Green State University years later. “We were the rubber capital of the world. We had for major companies here and Goodyear, by far, was the largest employer. It was tens of thousands of people who had a direct connection to the company.”

Oplinger assigned reporters Rick Reiff and Larry Pantages to write a brief story for the Tuesday paper about the uptick and the rumor that a New Jersey chemical company, GAF Corp., was making a play for the tire company.

“The activity created enough concern at Goodyear for chairman Robert E. Mercer to send a letter to all employees saying that the company is closely watching the stock market,” they wrote.

There was reason for concern but it originated far from the Jersey shore.

On Friday, Oct. 17, someone purchased 2.1 million shares of Goodyear stock. By that time, the Beacon’s business department was at full throttle, sometimes updating stories and changing headlines every few hours. Larry Williams became a driving force behind the coverage.

“The story could not have been made more appealing to Larry,” Dale Allen wrote in his unpublished memoir. “He understood the language of finance; terms I had read a few times but had not a clue what they meant. Arbitrageurs, junk bonds, leveraged buyouts – these were the things we read about that happened on Wall Street and other financial centers, but not in little old Akron, with its folksy title as the Rubber Capital of the World.

Dale noted that Larry found a willing partner in Oplinger, a fellow Eagle Scout. “Bringing Doug together with Larry Williams was like touching a match to a gentle mixture of kerosene and enthusiasm,” Allen wrote. “It seemed Doug had been waiting his whole career to find someone to light his fuse, to provide him with clarity and purpose, even if he did not really need much of a kick start.”

Together, and with the help of editors like John Greenman and Deb Van Tassel from Metro and more than 50 staffers, they produced the kind of news coverage that you’d expect to find in the Wall Street Journal, not the Akron Beacon Journal.

“Larry was modeling the Philadelphia Inquirer’s coverage of Three Mile Island,” recalled Greenman, who later became publisher of Knight Ridder’s paper in Columbus, Ga.

Thirty-nine reporters and eight photographers worked on that coverage, “many for weeks, and most with no days off and little sleep during and beyond the first, weeklong crisis,” recalled Michael Pakenham, associate editor of The Inquirer during TMI, writing 25 years later in the Baltimore Sun.

At the end, the Inquirer wrote a novella-length reconstruction, Greenman said. Many reporters contributed. Steve Lovelady wrote through their drafts, constructing and maintaining the narrative line. One editor, Larry, supervised.

Seven years later, Greenman noted, Larry modeled the Beacon’s efforts after the Inquirer’s.

************

The coverage ratcheted up after October 25, when British financier Sir James Goldsmith was identified as the potential buyer of Goodyear.

In addition to Goldsmith, Mercer and the other usual suspects like Akron Mayor Tom Sawyer and Congressman John Seiberling, the grandson of Goodyear’s founder, readers of the Beacon were introduced to characters we had never met before:

- Steve Seigfried, a Goodyear Aerospace engineer who represented the worst of Akron’s fears … he had already been laid off by three other companies. Now his latest job was in jeopardy, too.

- Jeffrey Berenson, a lead partner in Merrill Lynch’s merger and acquisition group who was identified as the primary architect of the takeover bid.

- Donald Walsh, a vice president at Akron’s Merrill Lynch brokerage who was feeling the heat from local residents for the corporate parent’s role in fueling the takeover attempt.

- Rufus Johnson, the janitor at the Goodyear barbershop whose comments about “Rambo time” bolstered the company’s spirits.

- Mark Blitstein, Goodyear’s director of investor relations, the company’s lead defender.

The business department had only three staffers when Dale Allen had arrived in 1980. He had tripled the team by 1986, but they were still working around the clock to keep pace with the Goodyear story.

Larry Pantages, Rick Rieff and Greg Gardner were the primary writers, with Glenn Proctor, Katie Byard, Ron Shinn and others taking us behind the scenes of board rooms, union halls and stock exchanges. The ’80s had ushered in an era of Wall Street greed unseen since the Roaring Twenties, and Akron understood the awful implications of a successful raid on the city’s largest employer. Goodyear assets would be sold off for a quick profit. Research and development and corporate philanthropy would likely be reduced, even halted. Workers would be laid off. The only winners would be Goldsmith, investment bankers and large shareholders with no stake in the city’s wellbeing. The losers would be the community at large.

Pantages remembers the day reporters scored a major coup: a phone interview with Goldsmith.

“The PR person we called almost every day, Lissa Perlman, had finally come through for us in setting that up. Maybe that was the interview where Goldsmith said, ‘I am a potential bringer of change,’ and we realized from his own lips what the threat to the city and the employees really was. I think he also clarified himself a little by adding something like, ‘I say ‘potential’ because nothing’s happened yet.’”

They rushed back to their desk to write the story for the final afternoon edition.

“When the papers came off the press, we grabbed a bundle and jumped in the car and drove to the Dubl Tyme restaurant right across the street from the HQ. We wanted to give the papers away and get reaction from workers during their lunch break. Much to our chagrin, we went into the place (I think it was me and Greg Gardner; maybe Reiff, too) and there were like three people in there. Not what we were hoping for.”

Business wasn’t the only angle getting coverage. The government team went full bore, with Bill Hershey reporting from Washington, D.C., Mary Grace Poidamani from Columbus and Charlene Nevada from Akron City Hall. Meanwhile metro reporters like Terry Oblander, Laura Haferd, Jim Carney and others were producing stories that showed the impact of the takeover bid on the community. Stories like:

- A church in Akron refusing to sell its 100 shares of Goodyear stock even though it needed $150,000 to buy a new roof.

- High school students starting a stock-buying campaign and writing letters to Congress and to Merrill Lynch.

- Joan Lukich, whose family had more than 200 years combined service at Goodyear, wearing a sandwich board and walking the streets of Akron, urging citizens to buy the company’s stock. “United We’ll Stand, Divided We’ll Fall,” was her message.

Gaylon White, a Goodyear PR exec, was reading every word. The former journalist was assigned to study media coverage of takeover attempts, both previous and present. He said the Beacon Journal’s coverage of the financial angles was almost as sophisticated as he had read in the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal. “But no major newspaper had ever covered the impact on the community like the Beacon did. … You guys ought to win a Pulitzer,” he told me back then.

White had other jobs, too. He was told by Corporate Communications Director William Newkirk to “be disruptive.” Goodyear wanted the media to show the public that Goldsmith wasn’t like us.

To that end, White enlisted a lot of help from Warner’s Corner, feeding me stories about Goldsmith’s lascivious lifestyle, shoeshine stand operator Rufus Johnson’s fighting words to Mercer (It’s Rambo time!) and a little item that went ‘round the world: The corporate raider had a distaste for anything rubber, especially rubber bands,

The guy is buying the world’s largest tiremaker and he has a rubber-phobia? My readers ate it up, especially after I published his New York address and urged them to send him gobs of rubber bands.

Maybe it worked. By mid-November, Mercer confided to associates that Goldsmith had won, that there was nothing the company could do to prevent the takeover. Yet a few days later, after facing a raucous crowd of Goodyear workers at a Congressional hearing and taking a tongue-lashing from Sieberling (“Who the hell are you?” he bellowed), Goldsmith walked away from the deal, selling back his stock to Goodyear for a $94 million profit – not bad for 10 weeks work.

Years later, Denis Kelly, a former Merrill Lynch executive, told me he never understood why Goldsmith settled when victory was at hand. “He was not the sort of fellow to back down.”

Then he paused as he recalled the events of those days.

“You know, he really did not like all those bags and bags of rubber bands showing up. That bothered him. He said, ‘Why are they sending me all those rubber bands?’ “

****************

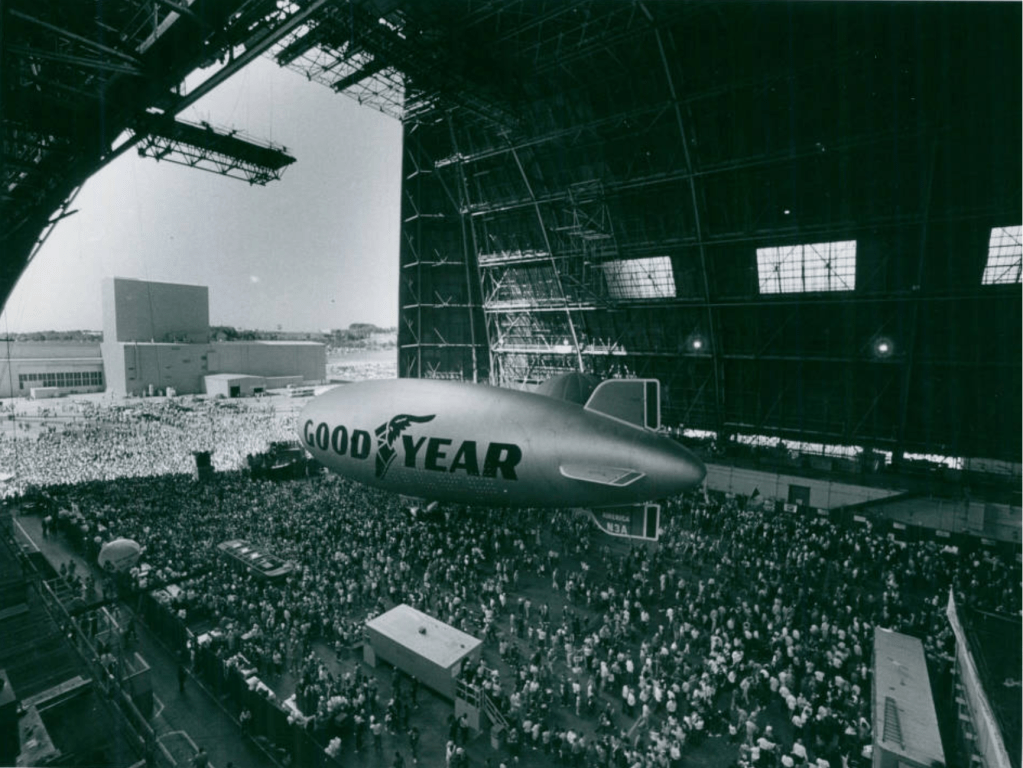

The Goodyear War was over on Thursday, November 22, though the reverberations from the takeover attempt would be felt for years to come. The next day, Larry Williams told me I would be the lead writer on a team that would produce a narrative reconstruction of what had just happened. I wasn’t sure why he chose me, given our disagreements over my columns. Maybe Dale had told him about some of the long-form stories I had written as religion writer. Perhaps it was because of the sources I had developed as the columnist. Regardless, I immediately began clipping and reading every story we had written about Goodyear since the day the Airdock was opened in September.

That weekend he and I met at the office and put together a detailed outline. Monday morning, November 24, we went to work.

By Monday evening, I was, in sports parlance, choking. Looking back now, the task we faced then seems almost impossible. Our goal was to fill an eight-page section with 15,000 to 20,000 words, much of it new reporting. And we had less than a week to finish. The section was scheduled to hit the newsstands on Sunday, Nov. 30, three days after Thanksgiving.

I was sensitive about my role on the project. The other reporters on the team were Melissa Johnston from the metro staff, Reiff and Pantages. Williams, Oplinger and Greenman were the editors.

There was also resentment among the other business writers who had been covering the story 24/7 for several weeks that I was on the team at all. And I admit, I had no idea how to spell or pronounce arbitrageur before I began the assignment. I thought a raider played for Oakland.

Maybe that is why I found myself struggling to find any words at all as I began to write the first chapter that Monday afternoon on my Commodore 64 in my home office. By midnight I still had nothing. By 2 a.m. Tuesday I had deleted blocks and blocks of copy. The green screen was still blank. My wife, Deb Van Tassel, told me to go to bed, start again tomorrow. I couldn’t do that. I couldn’t face the rest of them with empty pages. By 5 a.m. I was fading fast. Sometime between 5:30 and 6 a.m. I fell asleep on the couch next to my desk with not a word written.

I awoke re-energized and at dawn on Tuesday, Nov. 25. I started writing again at 7 a.m. The nap had re-energized me. By 9 a.m. I had a full draft of the first chapter. The solution had been simple. On Saturday, Sept. 13, 1986, Goodyear opened its airdock to the public for the first time in more than 50 years, according to news reports. More than 300,000 turned out to watch. Traffic was so bad that space hero John Glenn couldn’t reach the site. I placed each of the main characters at that moment in time in the drama that would play out as The Goodyear War. And the story began like this:

“The sun seemed to be shining on Akron as it had few times in recent history.

“At a few minutes past 11 a.m., the 600-ton front doors of the Goodyear Airdock began sliding apart ever so slowly.

“Hearts pounded as fast as the Akron’s Symphony Orchestra’s timpani drums rising to the first crescendo of the theme from 200l: A Space Odyssey.

“Men and women cried.

“It was a day to remember where you were.”

I showered quickly, got to work by 9:30 a.m., and no one on the team had any idea that I had pulled an all-nighter.

From there, the rest of the narrative started to flow.

I went to work on chapters two and three, which introduced our two main characters, raider Goldsmith and Goodyear’s Mercer.

As they continued to report, Reiff and Pantages worked on chapters four through six, which took us into this new world of finance that most of us knew little about. Yet they made it understandable for the folks in Akron. An excerpt:

“As the Goodyear rumors were circulating, another takeover battle was ending that would dramatize the new power of corporate raiders and portend bad news for Goodyear.

“Campeau Corp., a Canadian real estate firm, as in the process of a successful hostile takeover of the much bigger Allied Stores chain. Campeau’s revolutionary weapon was an equity contribution, some $1 billion from its investment banking firm, First Boston Corp. This was a departure from the usual takeover, in which a raider relied primarily on borrowing (often ‘junk bonds’) to pay the costs of a tender offer for all or some of the target company’s shares. The risk arbitrageurs, financial pros who invest in stocks of targeted companies, had to decide whether the potential reward of lining up with the raider offset the risk a deal would fall through.”

Six months earlier, not many of us would have had a clue what that meant. Now it was dinner conversation in Akron.

Still, there seemed an insurmountable among of work to finish by our Saturday night deadline.

Melissa Johnston continued to interview people in the community as I wrote. Pantages and Reiff scored an interview with Mercer, who accounted the most minute details of his lunch meeting with Goldsmith at the financier’s New York townhouse.

“Several bottles of wine were nearby in buckets,” they wrote.

“Goldsmith offered some to Mercer. He declined. ‘I don’t like to drink at noon,’ Mercer told Goldsmith.

“’Would you care for some water?’ Goldsmith asked.

“’That would be helpful,’ Mercer said.

“’Fizzy or otherwise,’ Goldsmith asked.

“’Otherwise,’ Mercer replied.”

Getting that kind of detail while still writing took time. We were working past midnight every day but by late Wednesday we realized we’d have to work through Thanksgiving Day, even if we already had plans.

“I remember walking into the newsroom at mid-morning on Thanksgiving Day to check on the story’s progress,” Allen recalled in his memoir. “The first person I saw was Larry Williams, his feet propped up on a desk in the middle of the newsroom, sound asleep, a file folder crammed with notes strewn across his lap. He had been at the paper throughout the previous night. For Larry, that was probably a very exciting way to spend Thanksgiving.”

Williams did give us two hours off in the afternoon to have dinner with our families. I remember swallowing some turkey and mashed potatoes with my wife and our 2-year-old, who most people knew then as Baby Corner. Then I must have crashed for a nap. Once again I was refreshed and back in the office by 5 p.m.

We continued to write until 4 o’clock Friday morning, completing all 11 chapters, some 20,000 words.

All that was left when we returned at noon was the final edit. Piece of cake, I assumed, even though I hadn’t had time for any cake or pie on the holiday. I was used to my copy sailing through the desk. How long could this take? Three or four more hours and we’d be done, I thought.

I’d never experienced the kind of deep dive into a story Larry Williams put us through for the next 20 hours. He questioned every assertion, wanted more information for every … . It was a clinic in professional editing.

But there were seven of us working on the final draft, and I know that when everyone tries to put his own fingerprints onto the text it can spoil a good story, so I sat down at the editing terminal and refused to budge through revisions of the first few chapters. I also said something else that did not endear me to my colleagues. “The first three chapters (which I had written) are in really good shape. Why don’t we speed things up by starting at chapter four?”

Uh, no. Larry Williams was not about to skip over a single word. We started with page one, line one, and worked our way meticulously through the draft, six others talking while I typed in most of their suggestions.

As the hours passed that night into morning, we discovered that chapter eight, which I hadn’t written, was based on a false premise, and had to be totally revised. I finally relinquished my seat and sacked out on a nearby couch as the other six hashed through a couple of thousand words.

By chapter nine, I was ready to go again and managed to regain control. But as we approached the finish, I realized we had no ending. Writers struggle over their lead, but often forget the significance of a great finish. I had nothing. Was I going to face another writer’s block?

Then one of my colleagues noted that Goldsmith had never been to Akron through the ordeal.

And there was our walk-off.

“Left behind was testimony to the enormous power of Goldsmith’s brand of capitalism,” we wrote. “He had terrified Akron without ever once setting foot in the city.”

*************

We finished the final draft at 8 a.m. on Saturday, Nov. 29. Then it was time for Executive News Editor Bruce Winges, Art Director Art Krummel, Assistant Managing Editor for News Colleen Murphy and their staffs to take over. Copy editor Mickey Porter line edited every word, with Larry Williams at his side, struggling to stay awake.

They had already begun some preparation earlier in the week, but they had no idea how much clay they would have to mold until they arrived much earlier than usual that day. Typically, Saturday nights are slow, most of the pages for the Sunday paper prepared in advance. But when Deb Van Tassel and I stopped by 44 E. Exchange St. that evening, it was as busy as an Election Night, with copy editors, page designers and artists, not to mention all the folks in the composing room, scurrying to make their 11 p.m. deadline.

The final product was simply outstanding. The layout of the eight-page section was clean, bold. The photos, surrounded by a gray border, jumped off the page. Artist Dennis Balogh’s Page 1 illustration captured the turmoil of the previous 10 weeks. And the headline said it all: “The Goodyear War … Hard to tell the winner from the loser.”

I guess our readers appreciated it, because we reprinted thousands of copies of the special section. We also sent copies of the section to journalists around the country. In those days before the internet, that was the only way to promote your own work, and we thought others might take notice.

They did.

Dale Allen was on the Pulitzer Prize Jury in March of 1987, one of dozens of journalists judging the best work of the previous year in the different categories. Dale was among the jurors judging the photography entries, but during a break for lunch he got some unexpected news.

“Seated next to me was an editor, whose name I have forgotten, who was a member of the jury charged with selecting the winner in the local general reporting category,” Dale wrote in his memoir. “It was in that category that we had submitted our coverage of the attempted takeover of Goodyear by Sir James Goldsmith.

“I had never met the juror before but, when we made our introductions, he told me that our Goodyear coverage was among the best he had seen that morning. He said something like this:

“’I haven’t seen all of the entries yet, but the one you guys submitted was the best I’ve seen so far.’ Then, he added something to the effect that he had never seen a story so well reported in all his years as a journalist.”

The names of the finalists are supposed to be kept secret, but back then, someone was always leaking them and Dale had a heads-up that we were on the list. The top three entries in each category are then sent to the Pulitzer’s Board of Directors, which selects the winner.

And when the prizes were announced on April 17, 1987, Dale already knew that outcome, courtesy of his former boss, Philadelphia Inquirer Editor Gene Roberts.

I wish he had given me at least a hint because I was out speaking to a community group and missed the initial celebration. But since Publisher John McMillion wouldn’t bend his policy of no alcohol in the newsroom, I was back in time when the champagne bottles were uncorked at the Cascade Holiday Inn that evening.

At first, the festivities seemed a little subdued; I thought it should be a little more like my days in sports, where the winning teams knew how to party. So I grabbed a bottle, popped the cork, and dumped the bubbly over Larry Williams’ head.

Many congratulatory telegrams followed. Robert Mercer wrote to Dale Allen: “The Beacon Journal saved Goodyear.”

Maybe. Maybe not. Because of Goldsmith, Goodyear was never the same company again. To pay for Goldsmith’s retreat, Goodyear had to sell off assets, including the company’s jewel, Goodyear Aerospace, and lay off workers. Within the next 10 years, it surrendered its crown as the world’s biggest tiremaker to Bridgestone of Japan.

Goldsmith had changed Akron forever.

Larry Williams brought change to the Beacon Journal newsroom as well. He only remained at the paper for three years before he was promoted to Knight Ridder’s Washington bureau. He died at age 74 on Dec. 9, 2019. But his legacy lives on with those who worked with him, even though not all of us appreciated his impact at the time.

We remained at odds over my column so I never really thanked him for the lessons learned that one long week reconstructing the Goodyear siege. But when I returned to editing a few years later, I hope I was able to infuse at least some of the same kind of passion and attention to detail into the writing of my reporters.

Others had a similar experience.

“I remember telling Dale that Larry put me into therapy,” John Greenman recalled about his daily story meetings with the managing editor.

“’But you became a strong assigning editor,’ Dale said.

“True enough.”

Indeed we were all better off for the experience.

Leave a comment