(Excerpted from “A Placed Called WriterL: Where the Conversation Was Always About Literary Journalism” copyright 2022 Jon Franklin, Lynn Franklin and Stuart Warner)

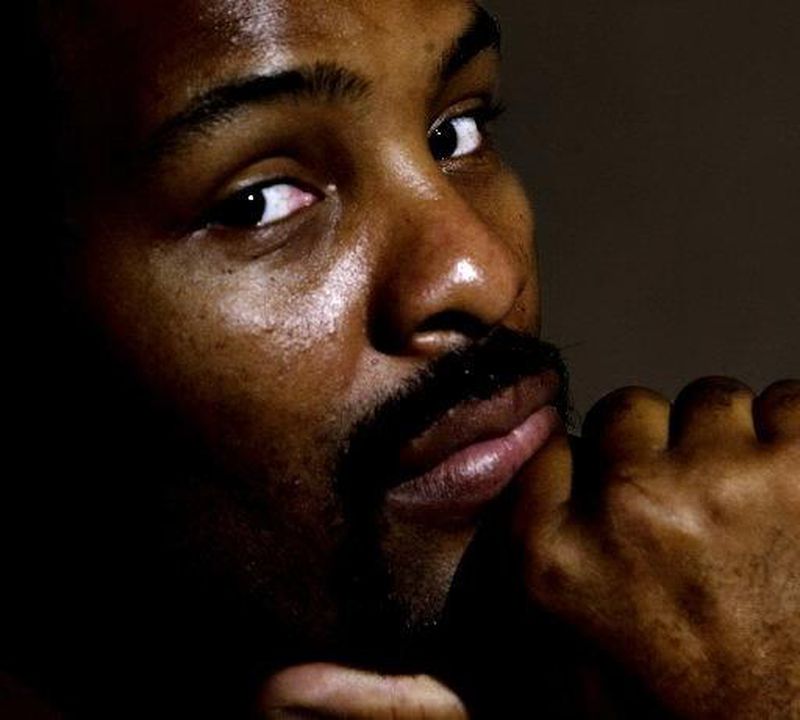

Photo of Michael Green by Eustacio Humphrey/The Plain Dealer 2002

Before Christmas of 2002, WriterL member Deborah Robson wrote an excellent critique of the writing techniques Connie Schultz used to develop the characters in her five-day, 25,000-word series “Burden of Innocence,” published in The Plain Dealer in Cleveland earlier that year. A Black man, Michael Green, spent 13 years in prison after he was falsely convicted of rape. Schultz followed him for a year after he was released. When the WriterL posting began again after the holiday break, Lynn Franklin wanted to pick up that discussion. Publisher and author Sol Stein along with Schultz, her editor Stuart Warner, and freelance writers M. Bozena Syska and Liz Duffrin and Jon Franklin provided a lively conversation about character development

Lynn Franklin: One of the things Deb mentioned was that Connie had managed to make all of the characters, even minor ones, three-dimensional.

People often ask me how one creates well-rounded characters, which would make it a good topic for discussion. Connie, could you tell us a little bit about how you did this? Were you consciously aware of the need to show all aspects of your characters, to make them real people? What details were you looking for in order to do this?

M. Bozena Syska: Could we start at the basics and define what makes a “three-dimensional character” or a “well-rounded character”?

Lynn Franklin: Bozena’s question sent me scurrying through our writing books, looking for a good definition. The most helpful came from Edith Wharton’s “The Writing of Fiction.” Originally published in 1924, it’s not a classic how-to book, but more of a series of essays on fiction at that time.

Wharton began the book talking about changes in fiction. Here is what she said about characters: “The next advance was made when the protagonists of this new inner drama were transformed from conventionalized puppets – the hero, the heroine, the villain, the heavy father and so on – into breathing and recognizable human beings.”

She goes on to describe recognizable characters as “… never types … but always sharply differentiated and particular human beings.”

So in the case of “Burden of Innocence,” Michael [Green] is not just “the hero.” He is a real human being, with real human angers, frustrations, successes and failures. Connie shows him changing from an angry young man into a mature adult, able to confront both the good and the bad in society.

Connie’s characterization of Michael is much deeper than, say, the classic fictional hard-boiled detectives, who tend to exist only on one level. Another example of shallow characterization is Harry Potter’s cousin in the first book of the series (I haven’t read the others so don’t know if the cousin is ever developed). All we see of Harry’s cousin is a spoiled, domineering tattletale. He is more of a caricature than a character.

Many – if not most – popular fiction, television and movie characters exist in a single dimension. This makes it difficult to recognize when we’re falling into the same trap in narrative journalism.

Sol Stein: Here are a number of craft ideas for creating characters readers cotton onto:

1. Try to find an eccentricity that characterizes. Most of the protagonists of fiction that have survived the century have more than a touch of eccentricity. It’s the one characteristic they have in common, though each eccentricity is different.

2. Pick a particularity and compare it to a known quantity. For example, “Archibald was Wilt Chamberlain tall.” Another way of doing it: “Frank is so tall he entered the room as if he expected the lintel to hit him, looking like a man with a perpetually stiff neck.”

3. Exaggeration of truthful attributes: “This distributor had a lawyer so short you wouldn’t be able to see him if he sat behind a desk. And he was Yul Brynner bald. But when he shook your hand you knew this fellow could squeeze an apple into apple juice.”

Another: “She stood sideways so people could see how thin she was.”

4. Pick on a part of a face or body. “It was difficult to make eye contact with her. She seemed to be looking for spots on the wall.”

5. Characterize through an action. Example: “The mayor moved through the crowd as if he were a basketball player determined to bounce his way to the basket.” Another: “He moved slowly across the room, age and arthritis made him seem brittle, but when he spoke – anywhere about anything – people stopped to listen as if Moses had come down with new commandments.”

You can characterize a place. I did a short piece for Ogonyok, the Time magazine of Russia, on 9/11. I assumed most of the readers hadn’t been to New York and the photos they’d seen did not give a picture of its overall vulnerability, not just the tall buildings. I characterized New York City as it might be seen from above, a skinny island with tentacles, the bridges and tunnels reaching out in all directions.

Connie Schultz: I was thrilled to see Sol Stein weigh in on character development before I could answer Lynn’s question because, unbeknownst to Mr. Stein, I am a devotee of his. I frequently turn to his book, “Stein on Writing” to jump start my own writing, and did so a lot while I was working on the “Burden of Innocence” series. I have shared his Chapter 12, “How to Show Instead of Tell,” with many of my colleagues, and it was my guide in developing my characters in a way that allowed them to move the story along.

It helped that I had an astute editor in Stuart Warner. Over the course of the writing, I frequently asked Stuart to fine-tune his radar for any signs of my romanticizing the main characters, particularly Michael. I knew that, were he and the others not fully human, their story would not be believable and I would have lapsed into melodrama. This was particularly challenging because the story was inherently dramatic.

Fortunately, Stuart was ever vigilant.

One of Stuart’s other strengths as an editor is his ability to see the overall arc of a story. One of my strengths is noticing what makes a person an individual. I apparently have an ear for cadence, which Stuart pointed out to me toward the end of the project. I often read aloud to “hear” the story, and Stuart said my voice, inflections and mannerisms were different for each of the characters, which I hadn’t even noticed. He was right. I had spent so much time with these people that I really did know their mannerisms and speech patterns. I also learned over time what was predictable behavior for them and what was unusual, perhaps even staged, which helped me know what to trust and what to leave out.

On rereading the above I realize that what I am really emphasizing here is spending time with people. As I’ve said in an earlier dispatch, I often sat on the floor, out of everyone’s line of vision. That allowed me to come as close to invisible as is humanly possible for a reporter, and then I would shut up and watch. I tend to write down everything I notice and not worry that I don’t yet know what matters and what is discardable. That comes later, when I’ve taken enough notes to see what surfaces as habitual behavior.

One of Stuart’s hard-and-fast rules for me stated at the very outset of reporting was that I could never say a character was feeling something. I had to show it, and that meant I had to really get to know the characters so that I could adequately interpret their actions and then describe them in a way that allowed readers to feel they knew what was in those characters’ heads.

Jon Franklin: This is well put, and since it’s a topic that perhaps more than other gives people fits, I hope she will go into this a little more. If you can’t simply say a person “feels bad” or “is happy,” then what do you say to show it?

Connie Schultz: Showing how a character was feeling, rather than simply saying it, was the single greatest challenge for me on the series. Repeatedly, my editor, Stuart Warner, would read a section and scrawl in the margin: “Show us this.” Excruciating. Infuriating. Exhilarating, when I finally got it.

Here are a couple of examples:

Example No. 1

The main character, Michael Green, faced the parole board four times and each time refused to confess to the rape that sent him to prison. He did this knowing that such an admission was the only way the parole board would release him early, but he refused because he was innocent.

I wanted to show his courage at this juncture, and so I spent hours interviewing him over and over again about that last walk to the parole board. I visited the prison and asked officials to take me on the exact walk Michael took, from his bunk to the parole board hearing room, at the exact time he made that walk. I wanted readers to feel his conflict and lack of freedom, and experience his resolve. Here’s the final version of that walk:

“On a sunny spring afternoon in 1999, Michael walked out of the prison pod door and squinted as he faced the winding path that cut across the yard of the Grafton Correctional Institution.

“His steps were slow and deliberate as he trudged the hundred paces or so to D Building. He looked around as he walked, taking in the expanse of grass where he was not allowed to step, the tidy beds of flowers he could not touch. He tilted his head just right so he could catch a glimpse of clear blue sky unmarred by the unforgiving loops of razor wire that had kept him caged for the last 11 years.

“He could walk this route at Grafton with his eyes closed. He walked this way to the lunchroom and adult education classes, to the gym and the Braille lab.

“Guards constantly monitored the path, barking at inmates: ‘Keep moving. Keep moving. Keep moving.’

“Today, it could also be the path to freedom. In D Building, the two parole board members were waiting.

“Michael had not served even half the 25-year sentence. Three times the parole board told him confessing to the 1988 rape and enrolling in the prison’s sex offenders program was the only way he’d get out before 2013. Three times, he said no.

“If he gave them a different answer this time, he could get out early.

“If he served the entire sentence, Michael would be 48 years old and have spent more than half his life in prison by the time he got out. ‘I don’t know how much more of this I can take,’ he told his sobbing mother, Annie Mandell, on the phone.

“The double doors to D Building were now in clear view. All Michael had to do was walk through them, look the two parole board members in the eyes and say, ‘All right, yes. Yes, I raped that woman.’

“A confession might get him out of prison, but he would never be free. He would be labeled a sexual predator and have to report to authorities every three months for the rest of his life. Neighbors and colleagues would be warned about him everywhere he went, anywhere in the country.

“It would be just another kind of prison. A prison with no parole, no escape, until the day he died.

“‘Progress, not regress,’ [fellow inmate] Arthur Freeman used to tell him. ‘The only way to go is to continue. Things will work out. That’s the spirit of innocence.’

“A guard buzzed Michael into D Building. Another ordered him to sit in the visitors room until he was called.

“Michael sat in the chair nearest the door and waited for a half-hour before he was ushered into tiny, windowless Room 294.

“Michael sat in the chair opposite the two women behind the table.

“‘Do what you’re going to do, he said. ‘You know you’re not going to parole me. You already know what you’re going to do.’

“One of them asked if he was willing to admit to the crime.

“Michael shook his head.

“‘I’m not confessing to something I did not do.’

“For the fourth time, the parole board rejected him.”

Example No. 2

When Michael first got out of prison, he was terrified that he could be picked up by police at whim and thrown back into prison. I wanted to show this fear, because it was real and he was constantly voicing it to me, which were quotes I couldn’t use. Then I found out about his first night out, when he couldn’t quite bring himself to leave the fenced-in area of his parents’ house. First Michael told me about it, then I asked his stepfather to describe that moment and his description was virtually identical to Michael’s. I interviewed them both about it several more times over a period of months, just to be sure the stories remained consistent.

This is the final version of the passage:

“The crowd didn’t disperse until after midnight. Michael joined his stepfather on the porch. They looked at each other and smiled. ‘Go ahead, son,’ Mandell said, pointing to the street.

“Michael walked down the front steps and stopped at the chain-link fence.

“He reached toward the gate, hesitated, pulled back.

“He reached again, pulled back.

“His stepfather winced as he watched. ‘It’s all right, son. You won’t be electrocuted. It’s just a fence, a plain old fence.’

“Michael smiled sheepishly. ‘This is far enough for now,’ he said, turning back toward the house. ‘Maybe later.’

“Man, to take a late-night walk through the old neighborhood. He used to do that all the time. He would stomp through the tangle of weeds and wildflowers on vacant lots, breathe in deep as he wove in and out of the cool, musty woods along Martin Luther King Jr. Drive.

“But he didn’t have a single piece of identification on him, nothing to distinguish him from any other Black man the cops might feel like picking up. No one could talk him out of that fear.

“Michael walked back up the steps.

“‘Tomorrow, Pops,’ he said. ‘Maybe I’ll take a walk tomorrow.’”

Lisa (last name withheld): Perhaps the answer (to character development) lies in an old reporting exercise. I’ve benefited greatly over the years from the exercise of asking myself “How do you know?” in nearly every story (aka “prove it”). And I think it applies as much to writing as to reporting. How do you know he’s happy?

- He broke into a deep, satisfying smile that didn’t entirely leave his face for hours.

- He whistled.

- Jokes were made.

- Friends like to hang around him because they always seem to have a good time when he’s there.

That’s how you show it and not tell it.

Stuart Warner: I don’t mean to argue with what Lisa said as much as to augment it. I believe we have to be even more vigilant in the unattributed narrative because we are asking for a lot of trust from our readers. If you say that smile didn’t entirely leave his face for hours, then you should have been there to see it didn’t go away. Or at least confirm with two sources that it didn’t. If we say friends “seem” to have a good time, again, we better confirm that they enjoy his company. Better yet, show their actions of having a good time. Or repeat the jokes that were made. Such is the burden of the nonfiction narrative writer. If you say the sky was blue and you weren’t there, you darn sure better have the weather report from that exact moment in time because somebody, somewhere is going to remember.

Liz Duffrin: I have questions for Connie Schultz. How do you get the subjects of your narrative to recall events in such vivid detail? For instance, how did you find out that Michael’s stepfather winced as he watched his stepson reach his hand toward the gate? How do you know that Michael’s smile was sheepish or that he tilted his head just right to catch an unobstructed glimpse of sky? Did you have them act it out? Do you have a particular technique for questioning them? And how on earth do you get people to put up with you while you squeeze that kind of detail out of them?

Connie Schultz: Whenever possible, I actually do ask the subjects to act out a scenario when all involved agree happened. For example, Michael and his stepfather agreed to walk outside with me and show me how that evening’s moment at the fence unfolded. Understand, however, that this is not something I asked of them early on. I spent months just hanging out, quietly taking notes and asking questions sparingly at times so as not to alienate them or make them acutely aware of this reporter’s presence at all times. By the time they reenacted the fence scene, I had known them for months, and they had grown accustomed to my questions and appreciated my desire to get it exactly right.

I had earned their trust and engaged them in the effort to portray as accurately as possible their story, not mine. Also, I knew them well enough at that point to expect certain facial expressions and body gestures. I was familiar with their physical quirks, if you will, having studied them for nearly a year.

I had to smile at the question regarding how I get people to put up with me. It really is a matter of earning their trust and then encouraging them to invest in the outcome almost as much as I.

With the prison walk scene, I asked Michael to describe the moment – when and where – on his walk to the parole board hearing when he could catch a glimpse of that sky. Then I visited the prison and took the exact route, watching the sky just as he did. Finally, I checked with the National Weather Service to see what the weather was like when he made that walk.

I regularly told Michael and his family, “I want this to be your story, not a white woman’s account of your story.” Over time, they understood what I meant, and almost always they were actually grateful for my attention to detail. I endured my share of ribbing from them, of course, and Michael does a pretty impressive imitation of me rattling off the questions: “OK, so you were standing, where? Uh-huh, and what were you wearing? When you said that, how did he react? …”

I asked my project editor, Stuart Warner, to describe his role in this process. He adds the following:

Stuart Warner: It’s also important to remember that this story was edited with the same scrutiny an investigative story is edited.

Just as an investigative editor does document checks on every fact, I asked Connie to verify every incident or anything that could be subjective. But except for trial transcripts and a few other legal papers, the only documents were her exhaustive collection of notes. How did Connie know he saw “Connecticut” on the flip side of the new quarter? Did the guards really say, “Keep moving. Keep moving.”? [Connie went there and heard them herself].

We debated every adjective. How would we describe Michael’s fiancé. White women might think she was a plus size. Black women might not. (We finally decided to let that one go.)

Any time there was a discrepancy, we went back and asked again. And again. Michael’s stepfather said he found the evidence kit in a box. The clerk insisted that all evidence kits are put in plastic bags. By checking with even more sources we found that it was indeed in a box, and the reason that it was may lead us to another story, which we can’t discuss here.

In short, narrative writing can require even more reporting and re-reporting than even the most complicated investigative stories.

Postscript from Stuart Warner: A few days after this conversation occurred on WriterL in January of 2003, Roderick Rhodes turned himself in to Cleveland police for the rape of the cancer patient for which Michael Green was convicted. Rhodes said he was a heavy drug user at the time the rape was committed in 1988 and didn’t even remember it until he read Connie Schultz’s series, Burden of Innocence, which was published over five days in October 2002. Cleveland police scoffed at his confession, but the DNA that had not been used as evidence in 1988 proved that Rhodes was guilty. He was convicted and served five years in prison. Michael received more than $1 million from the state for false conviction and another $1 million from the city of Cleveland after it was proven, as the series revealed, that the medical examiner falsified evidence to obtain the conviction.

In March of 2003, the series won the Robert F. Kennedy Award for social justice reporting and Best in Show at the National Headliners competition. It was a finalist for the 2003 Pulitzer Prize for feature writing. Two years later, Schultz’s columns on Green’s battle with the state for reparations were part of her entry that won the Pulitzer for commentary. She is now a national columnist for USA Today and her first novel, “The Daughters of Erietown,” made The New York Times bestseller list. She credits what she learned about developing nonfiction characters with creating her fictional characters.

Leave a comment